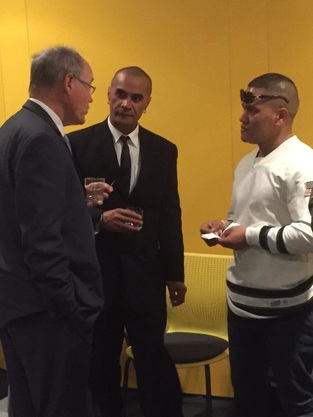

Don Brash speak with Teina Pora and Mikaere Oketpa (aka Michael October) before speaking at the launch of NZPIP

Don Brash speak with Teina Pora and Mikaere Oketpa (aka Michael October) before speaking at the launch of NZPIP Forty years ago, I met Pat Booth for the first time. He was working to prove that Arthur Allan Thomas had been wrongly convicted, and that to gain his conviction the Police had fabricated evidence. I was shocked. I had been brought up to believe that the New Zealand Police were beyond reproach in every respect.

Pat Booth told me of a number of cases where he was quite certain that the Police had planted evidence. One I remember involved a man Pat interviewed in jail. The man had been convicted of breaking into a safe and stealing its contents. He told Pat that when the Police first arrested him, they searched his car for incriminating evidence, and found none. They later took him and his car to the Police station, and searched the car again. Lo and behold, this time they found some detonators underneath the driver’s seat. The man didn’t claim to be innocent – indeed, he admitted his guilt – but, as he told Pat, “I don’t drive around with a bunch of detonators underneath me bum!”

I still believe that the New Zealand Police force is among the very best in the world – largely free of corruption and largely free of the temptation to plant incriminating evidence.

I similarly believe that the New Zealand justice system is among the very best in the world.

But we all know that miscarriages of justice sometimes occur. Police are sometimes guilty of planting evidence to incriminate people whose guilt they are convinced of. They are sometimes influenced by bias and preconceptions. Juries and judges sometimes get it wrong. Why does that happen? Mainly because, like the rest of us, Police, judges and juries are human. They can and do make mistakes.

In the United States, more than 300 people on death row have been exonerated after being found to have been wrongly convicted. There is little doubt that many others have been executed for crimes they did not commit. Since 1989, a total of 1250 innocent prisoners have been released according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

In the United Kingdom, the Criminal Cases Review Commission was set up in the mid-nineties following public disquiet over a number of unsound convictions dating back to the seventies. To date, over 70% of the cases which the Commission has referred back to the Court of Appeal had their appeal upheld. This British experience has led Sir Thomas Thorp to estimate that there may be 20 people wrongly convicted in New Zealand jails at any one time.

And certainly I know of no reason to believe that the situation in New Zealand would be fundamentally different to that in the United Kingdom.

We know that Arthur Allan Thomas was convicted on planted evidence.

We know that Teina Pora was wrongly convicted.

We know that there are very grave doubts about the soundness of Peter Ellis’s conviction.

It was reading Lynley Hood’s remarkable book, “A City Possessed”, which convinced me that there was something very seriously wrong with Peter Ellis’s conviction. The book shocked me profoundly. There seemed to be just so many flaws in the case against Peter Ellis that I found it utterly incomprehensible how any court could have found him guilty – and simultaneously see nothing odd about the charges against four women initially charged alongside him being withdrawn.

The book prompted Katherine Rich and me to launch a petition calling for an independent review of Peter’s conviction in 2003. We were both in Parliament at the time and had limited time to canvass for signatures. Katherine thought we might get 30 or 40 signatures. I thought we might get more than 100. In the event, we got more than 4,000 signatures without even trying very hard.

And it was not just the number of signatures the petition attracted. It was the particular people who signed the petition – David Lange, Mike Moore, Winston Peters, Rodney Hide, Judith Collins, Clem Simich, David Parker, Chris Finlayson, 11 law professors, umpteen QCs – not the kind of people who lightly sign petitions of any kind.

Despite the total absence of any solid evidence that a crime had actually been committed by anybody, despite the utterly preposterous nature of some of the assertions of the very young children who testified to what they remembered, despite the now irrefutable evidence that the memory of very young children is often highly unreliable, despite one of the key Crown witnesses recanting on her evidence subsequent to the original trial, in the eyes of the justice system Peter Ellis remains a convicted child molester, and his life has been utterly ruined.

And the impact of that conviction has been extremely serious not just for Peter’s life. There can’t be much doubt that the conviction has deterred many men from having anything to do with early childhood education, with the inevitable result that far too many children have no positive contact with male role models until much later in life. The social costs of the conviction have therefore been enormous.

Leave it to the court system to sort out, argue those who see no need to establish a body like the UK Criminal Cases Review Commission in New Zealand.

But as Herald writer Brian Rudman noted in an article calling for the establishment of a Criminal Cases Review Commission in New Zealand late last year, “the problem with leaving it to the court system is the emphasis is about process, and did the lower courts make any errors in law, or break any trial conventions”, rather than making any wide-ranging inquiry as to whether a miscarriage of justice has occurred.[1]

I still strongly believe there needs to be an independent inquiry into Peter Ellis’s conviction but I also believe strongly that New Zealand needs a Criminal Cases Review Commission.

(For more information on the NZPIP see the website)

[1] New Zealand Herald, 29 October 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed