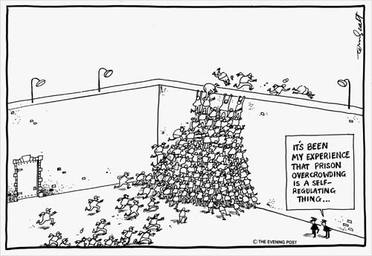

Cartoon sourced from Te Ara

Cartoon sourced from Te Ara For many years, prisons have been seen as the answer to New Zealand’s social ills. In a phenomenon so well defined that it was given a name, both the Left and the Right engaged in ‘Penal Populism’ – a game of one-upmanship to see which party was the toughest on crime. Much credit for this goes to a kindly and well-intentioned cow cocky from the Hawkes Bay who formed a tremendously powerful and equally unthinking lobby group called the Sensible Sentencing Trust. This group held tremendous sway over a public completely taken by the idea that a simple solution could combat complex phenomena.

With an imprisonment rate per head of population almost 40 percent higher than that of Australia, New Zealand showed a real zeal for locking people up. Few people were troubled by the inconvenient and demonstrable fact that prison wasn’t working. While we quite rightly sated a desire to punish, we were creating more, not fewer, victims. Given pause to think, this is a despicable thing to accomplish. Recidivism rates offer statistical evidence. Of those under the age of 20 we have locked up, for example, 91 percent have been reconvicted and 65 percent have returned to prison. More crime, of course, means more victims.

Academics were pointing this out, albeit too quietly, but the country was in no mood to listen. At least until 2011 when Bill English decried prisons as “a moral and fiscal failure”. Nothing, it seems, tunes the ethical compass of a Finance Minister like a global financial crisis. From that point on, the National government began to act in brave and ambitious ways. They did so quietly in case anybody questioned the U-turn.

Quicker to act was a group of liberal Christian do-gooders. They established the Pathway Trust in 1996 and a ‘total reintegration strategy’ for prisoners in 2008. Initially the programme was devised off the hoof, with little more than a few hunches and a lot of prayer, but later it began to incorporate principles of Desistance Theory and the Good Lives Model.

After five years the Pathway team were convinced they were on to a winner – but that’s not surprising. Numerous groups work with prisoners and herald success, but most programmes don’t work. In fact, in a hat to tip to Murphy’s Law, many actually increase offending. Pathway decided to test their programme and this is where my off-sider Ben Elley from iRS and me come in.

The primary research question was straightforward: did the prisoners who undertook the Pathway programme stay crime free at greater frequency than those who didn’t? A cleaner outcome could scarcely be devised in the social sciences.

Department of Corrections data record that 54 percent of released prisoners are reconvicted of new offences and 35 percent return to prison within 12 months. Of the Pathway sample, the rates were 36 percent reconvicted and 20 percent re-imprisoned. In other words, those people involved with the programme were 33.3 percent less likely to be reconvicted and 42.9 percent less likely to be re-imprisoned than those not on the programme. Furthermore, among those who were reconvicted, their offences tended to be much less serious than those they committed prior to engaging with Pathway.

These data suggest that the programme was working – and working well.

There are some important caveats on these findings, primarily that the total number of clients was small (n=59), meaning that these results should be seen as indicative rather than conclusive. Confirmation awaits analysis of a larger cohort measured over a longer timeframe. This, however, does not diminish the fact that these initial findings are extremely encouraging. Not least by those concerned by a tax burden. It is now commonly noted that every year each prisoner costs around $100,000, a figure that doesn’t include the capital costs of building prisons. The Department of Corrections has an annual budget of 1.2 billion.

Less well known is how significant even marginal success is in creating cost savings. Pathway clients who reoffend, but who commit less serious crime, will still bring joy to the Treasury, as their figures show that those offences typical of Pathway clients before entering the programme tend to be have a high cost, ranging between $72,130 (sexual offences) and $23,100 (robbery), whereas those less serious offences undertaken by those post-programme Pathway clients who do reoffend tend to be less costly, ranging between $5,780 (drug offences) and $1,300 (theft). Change in criminality most often doesn’t happen cleanly (like weight loss or stopping smoking), so small slips ups are actually progress under the desistance model. Reduced offending, in time, leads to no offending.

But the numbers around reducing or not offending are one thing, real value exists in knowing what actually worked in reducing or stopping people committing crime. And this we uncovered by conducting interviews with Pathway clients – including those who had successfully stayed out of prison and those who had not.

The majority of our subjects reported histories of extremely negative, unhappy, and crime-dominated lifestyles, and many had undertaken long stretches in prison. Two interviewees had life sentences and another had done nine stints in jail from 18 years of age before entering the programme at 35. Participants reported that both their life histories and long jail terms had created a mentality that inhibited reform. They also shared a perception that society was unable or unwilling to give them a chance.

Participants noted a range of factors that they found to be important depending on their needs, for example alcohol and drug support or housing assistance. This is hardly surprising: if you have a drug problem and you get help with it then that’s going to be useful. The major aspect of the programme, however, was the support provided by the reintegration staff. Having somebody to turn to was the key to everything.

For most people reading this, it will be odd to think that many people don’t have support networks. I know that if I fall over for whatever reason I will have a large number of people I could rely on for help. Many people have none. None. And often when they do have support it is criminal or anti-social in nature. They rely on those who will lead them to crime.

At this point some people will say, that these people just need to have greater fortitude, make the decision to change and stick with it. Individual responsibility and all that. But anybody who has tried to lose weight, give up smoking, or change careers knows that even small changes in one’s life are often difficult to achieve. To fundamentally change one’s entire life and learning is a big task. Unsurprisingly, therefore we found that people needed help to achieve it.

And in case you missed it, right there is the key. So long as we see prison and individual responsibility as the answer to crime we will fail in our goal of reducing the number of victims. Take a couple of minutes to hear Barry’s story. I don’t know if it will open your heart, but I demand you open your mind. We need to be smarter not tougher on crime.

Pathway Trust will tell you God plays a big part in their success. All I can say is science proved it. And Barry speaks to it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed