___________________

The Epitaph Riders was formed in 1969 by a bunch of friends in a large house on Geraldine Street in Christchurch. Although there was a nominal president, Ross Jennings, initially there were few, if any, rules and no club structure. Like other outlaw motorcycle clubs in the South Island around this time (such as the Antarctic Angels of Invercargill and the Highwaymen of Timaru), and before they had significant contact with the more mature scene in the North Island, the Epitaph Riders took their cues largely from popular media. A member of the Riders recalled:

That book Hell’s Angels that Hunter Thompson I think wrote – that was out and we just – it all just sort of happened and we were all running around with this stuff [patches] on our back and um that’s how it started . . . We didn’t [know what we were doing] we were just a bunch of young guys, mate, that just hung around. We’re all fuckin’ 17, 18, the oldest would have been 21 probably. And it’s just the way it happened. We all used to meet on Friday nights and just go drink piss – it just started from there . . . Drink piss and fuck women. There was nothing else in life – riding bikes.

By 1973, however, the Epitaph Riders had matured significantly. The group was now comprised of young men from working-class backgrounds aged in their late teens to mid-twenties, and boasted some 22 patched members, including an executive consisting of a president, two vice presidents and a sergeant at arms. By this time, rules were also in place to ensure the club was a significant part of its members’ lives.

The increasing commitment to the club is reflected in a decision made in August 1973 making it compulsory for members to attend weekly meetings and a Sunday run as well as any parties the group decided to have. A rented flat was used as a clubhouse and weekly fees of two dollars were collected along with an additional one-dollar levy for beer on the Sunday rides. Fees were used for club expenses including subsidising major runs, helping members in trouble, and paying fines incurred during group activities. The communal behaviours of the group are, in substantial measure, a reflection of the wider social environment of the time. The club’s colours were also held in significant esteem. While colours were only compulsorily worn on runs, it was against club rules to deny being a member of the club. In the mid-1970s, one member even rode to teachers’ training college on his bike wearing his patch. It would be impossible to conceive of this occurring now without a public uproar, reflecting a dramatic change in attitudes toward such groups.

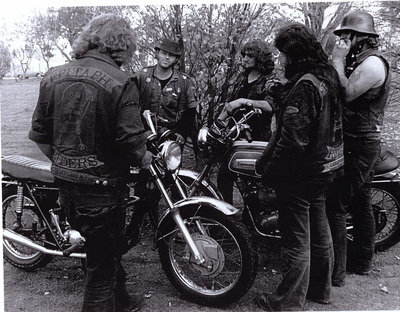

Although the Epitaph Riders’ motorcycles were kept meticulously clean, members had adopted the ‘ridgies’ style, that was by this time standard within the gang scene. ‘Ridgies’ (derived from ‘originals’) is the set of original clothing a member was wearing when he was initiated into the gang and given his colours. These clothes were regarded as sacred and never washed so they soon became dirty and tatty. The custom may have come about initially as an inevitable outcome of members working on their machines and travelling and sleeping rough while on runs. It soon, however, became the desired look – a form of gang uniform. Yet ridgies were also more than a uniform. Grease from vehicle breakdowns, dirt from motorcycle trips around New Zealand, blood from fights and fluids from sexual encounters all mixed together to become part of a subcultural, or countercultural, style imbibed with symbolic meaning. As one Mongrel Mob member put it: ‘To wash them would be to wipe away the memory of our conquests and history.’ When ridgies fell apart, they were either patched up or a similar item of clothing was sewn underneath.

As they were for all gangs, the clothes undoubtedly represented a visible expression of the Epitaph Riders’ antisocial stance, and many of the members had convictions for petty offences. In what is now a common – and important – refrain, the police were perceived as an enemy and many of the club’s members believed they were unfairly targeted and victimised. Fighting was a significant activity that demonstrated machismo as well as instilling group loyalty that the club actively fostered. With an ‘all for one, and one for all’ philosophy, if any member got into a fight, regardless of fault, other members were required to back him up. This fighting ethos was central to enhancing the group’s reputation and ensuring that people thought twice about confronting its members. In Christchurch, the Riders engaged in many conflicts with other fledgling gangs, and particularly budding outlaw clubs. Like other Biker Federation clubs, the Epitaph Riders had determined that they would be the only outlaw club in their city. In the early 1970s, at least three other groups – the Apostles, the Heaven’s Outcasts, and the Highwaymen – were beaten or intimidated by the Riders and had their colours taken. Vanquished, these groups disappeared and the Riders maintained a firm grip on Christchurch. By 1973, the Epitaph Riders were a well-established outlaw motorcycle club, and with their frequent travels around the country it is widely acknowledged by those in the scene at the time that they held a reputation as among the country’s staunchest, and consequently one of the most respected, groups within the biker – and indeed the entire gang – community. In biker parlance, they were class.

[References for the above can be found in PATCHED - likewise the story of their dramatic war with the Devils Henchmen].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed